From The Archives: Merle Haggard, Son of Bakersfield

Note: I wrote a bunch of stuff before posting the actual article. You know, like recipe sites, except I heard some of those guys make money. So just scroll down a thousand words for the actual thing you clicked on. Which reminds me, consider a paid subscription if you like what I do. Cotton is down to a quarter a pound and I’m busted.

Getting too wistful will kill you, so I want to say up front that I’m not sharing today’s archival post because I’m wistful. It’s my obituary for Merle Haggard, originally posted on MTV, and I wanted to show it to an editor. But I was disgusted to discover that not only did MTV remove it from their website, they don’t even play music videos anymore.

Anyway, here it is, pulled from my personal collection (Wayback Machine). It was almost nine years ago now but it still feels like yesterday. I found out in the car and just pulled over and sat there despondent somewhere in North Hollywood. Merle Haggard was the greatest country singer/songwriter who ever lived, an almost-academic belief that I could write a really boring thesis about. But he was also my hometown anchor, the guy I could point to and say hey, the Bakersfield I knew is still here. So when I was asked to write about him, I was pretty well destroyed. I’m thankful for it though, because it gave me a direction for my grief, let it vent.

I can’t actually read this piece ever again because it was really me working through the feeling that the Bakersfield I knew, old labor camps and canals and Dust Bowl grit, was going away, and I was doing that thing where you realize your concept of home is going away and you have to make your own now. And you won’t ever get there. You’ll never feel home in the same way ever again. All you’ve got is memory, a place where you can’t live.

My grandparents have died since then. They’re buried by Buck Owens but it’s off a really annoying freeway exit so I don’t go to the cemetery. We sold my grandpa’s house, and it was hilarious how the realtor staged the tour pictures like an Airbnb but couldn’t remotely get rid of all the rectangular lines on the wall where picture frames prevented nicotine staining. I hope the new owners never even once feel haunted by an old ghost from Arkansas who forever walks around the yard with a hose, spraying the dirt so it doesn’t blow through the windows, softly mumbling “Oh, My Darling Clementine” until the end of time and the stars crash. I’d hate that. Oh and if I die, it would be awful if they found me out in the shed holding up a bunch of different huge knives and asking “why did he have so many knives?” If they don’t cut down the lemon tree then hopefully it won’t happen.

I don’t go to Bakersfield now. I don’t know anybody there. I used to jump between Bakersfield and L.A. every couple weekends for most of my adult life. The muscle memory still kicks in on Saturdays when the weather’s nice and I’ll restlessly pace around for an hour or two before remembering “oh right, this is the part where I’m supposed to drive too fast and do some Dust Bowl cosplay and have no opinions about David Zaslav.” I miss it but it’s not there anymore.

There are still some cool landmarks though. There are legit historic buildings and businesses and surviving midcentury stuff, these little time portals that still look like Los Angeles used to look, and California used to look. Andre’s, that big shoe, the old coffee shops and roadside burger shacks, Dewar’s, Woolworth’s, Smith’s, Happy Jack’s, the 24th Street Cafe, they’re worth the detour if you made a mistake or two and wound up there. But the “this is the edge of the earth” existentialism it used to have has long been phased out and replaced with big box stores and vacuum-sealed tract houses and ominous undecorated corporate buildings called like AGGISTICS, which is a totally different breed of existentialism. I think it’s the Pynchon kind but I haven’t read him.

Anyway, the piece. It’s a snapshot of time. How I felt at the moment (bad, I felt bad). There were no edits. But it’s all true, which is nice. I’m glad I didn’t go through that phase a bunch of writers go through where you lie a lot. I’m proud of my moral compass that only let me lie by omission, so I could have plausible deniability.

If I were writing this now, I’d still tell people how I felt (bad), but I’d probably play more offense, try harder to explain why Merle’s writing was so good, why Merle and California country felt like freedom from Nashville and the church, why it was so damn western. How it did and still does feel like punk rock after you’ve had enough of the pretty formalism out in Tennessee. How tight his band was. (Austin City Limits ‘78, get after it.)

Merle Haggard was as much a big screamin’ deal as Hank Williams but he never got his due in the same way. The press is bored by the survivors. He lived long enough for local shows to be something people blew off because they didn’t want to spend $40 that weekend. There was no MTV-ready comeback. He was kind of a hardass. People say he didn’t like his fans, and they say that about Bob Dylan now, but like Bob Dylan, he played concerts everywhere all the time, which is all that really matters. I mean, he also didn’t like his fans, but he didn’t retire so my rebuttal is so? I just want people to know he was the best who ever did it.

This article was funny because MTV hired me to cover the 2016 election and go to the conventions and write real hard about it but this is the only thing I published there that anybody ever mentions anymore. Norm Macdonald said it was sad and beautiful. Judd Apatow liked it but didn’t give me a job for some reason. Somebody told me it was in the Grammy Museum for a minute, which probably isn’t true. Dave Alvin told me it was the best piece about Merle he’d ever read. I felt like I had this new, tangible moral obligation to carry the torch for Bakersfield writing and the Bakersfield sound, a tangible moral obligation I ignored as fast as I could.

My main memory of this piece though, is when an old family friend, who knew Merle in the ‘60s and ‘70s, silently read a printed-out copy for what felt like an hour but was probably 3 minutes, shed exactly one tear, wiped it off, and never talked to me again. I have no idea what he was thinking but it’s better that way.

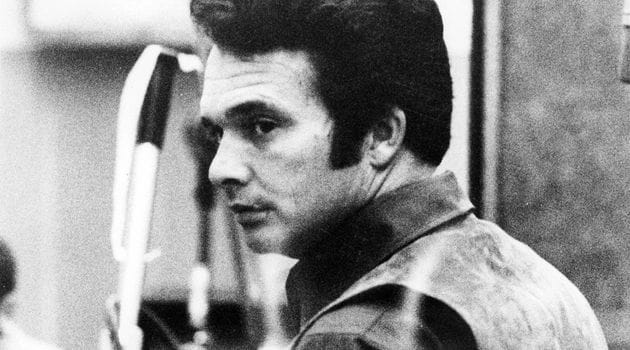

Merle Haggard, Son of Bakersfield

(Originally published on 04/07/2016)

I’m from East Bakersfield, right at the end of Highway 58 before it takes you to the desert. My grandma cleaned houses until her body wouldn’t let her anymore. My grandpa is a retired truck driver and smokes a pack a day. It used to be Camel Straights but they got to be too expensive so now he buys Seneca, king size, unfiltered, at a reservation in Porterville. And I’ve never seen him happier than when he said he saw Merle Haggard’s steel guitarist there.

I was born into country music. I didn’t have a say in the matter. I was given my grandpa’s surplus Merle Haggard LPs as birthday presents before I even knew what rock and roll was. I knew the words to “Mama Tried” a solid decade before I heard of Elvis. When I look back on my childhood, my fondest memories are of sitting in my grandpa’s tiny yellowing living room in a cloud of smoke listening to Merle Haggard records while he drank coffee and said almost nothing. Merle Haggard wasn’t the beginning and the end of country music — he was the beginning and the end of music. Period.

I knew he’d been sick this last few months. But he had been sick before. It was expected. He treated his body like hell. But he always survived the mythological country music vices. The straight-out-of-the-bottle whiskey guzzling, the mountains of cigarettes, the shoeboxes full of cocaine. He had lung cancer and beat it. He was unkillable.

But by Easter Sunday, sitting at a family reunion with people who knew Merle Haggard personally, well enough to call him Merle without pretense, it felt different. Merle was very old now. He was about to turn 79. He had pneumonia, and he’d been in the hospital, and now he was canceling tour dates. I asked my uncle if I should be worried this time.

“Let’s put it this way: His bus driver retired.”

The air went out of the room. He’d had the same bus driver longer than I’d been alive.

“He likes being off the road,” my uncle continued. “He’s discovering Netflix now. He called me up and asked if I’d heard of House of Cards. I said ’Yep, I sure did, three years ago, pal.’ I figure he’s about twenty years behind on television. He spent way too much time in that damn bus.”

We all laughed, but we were laughing to keep from saying good-bye. If Merle Haggard was off the road, Merle Haggard was about to die.

When I finally got the inevitable news, a thousand images came into my head at once. The image of him approaching my mom at Safeway and asking her what kind of salt he should buy. The image of his tour bus pulling away from a Walmart Supercenter at midnight as the employees stood at the door dead silent. The image of him sitting at a corner booth in his go-to greasy spoon, eating chicken fried steak on a Sunday, while I sat listening to the place turn suddenly into a church. The image of two twentysomething dudes sneaking slugs of whiskey in the men’s room at one of his last hometown concerts, bragging that they shared his weed doctor.

When Johnny Cash died, it was like part of the American landscape vanished, like we lost the Grand Canyon. But when Merle Haggard died, speaking as someone born in Bakersfield and descended from Okies and Arkies who knew exactly what the Dust Bowl was, it was like losing a member of my immediate family, like there was one less place to set at my grandma’s table.

Because Merle Haggard wasn’t a singer to us. He wasn’t a songwriter. We never called him the “working man’s poet” or waxed philosophic about his role in the Bakersfield sound and how it shaped rock and roll. He was too important for that. He was the center of our culture. He was a part of every family gathering and every drive. A man who not only sang about my family, but to my family, without mythologizing or patronizing or getting any of the details wrong. To use my grandma’s phrase, “he sang my life.”

Haggard’s songs were tough, undecorated songs about the struggles of common people who were barely getting by in a country that wasn’t particularly receptive to them. They made you feel like somebody was in your corner through the struggle just to exist. He empathized with people who worked with their hands. And he never got patronizing about it, because he knew what it was like. He’d been there. You could hear in his smoke- and alcohol-ravaged voice and unaffected singing style that he had been there.

What Merle Haggard had is what separated Bakersfield country from Nashville country. He didn’t try to sing pretty, he tried to sing honest. He tried to write honest. The great Merle Haggard songs, like “Mama Tried” or “Workin’ Man Blues” or “The Bottle Let Me Down” or “Kern River,” they didn’t dress up for you at all. They sounded like they’d been kicked around by dust devils for a few months before he recorded them. They sounded beat up and hard-traveled. And that worked. He just went and told his story and played his songs. He could play any city in the country by being exactly who he said he was.

That made it all right to be from Bakersfield when a lot of people weren’t all right with that. When people might physically recoil at your destitution or wonder if you could read. Here in your corner was Merle, and he was truthful about where he came from, about being an ex-con who had lived in a boxcar in Oildale, and people were fine with him. He legitimized people like my grandparents and all of the other displaced people in the parts of California people try to get away from. He legitimized everybody who got up before sunrise to drive trucks or pick cotton in some of the most desolate towns in America. Towns where it never rained. Towns of dirt and canals and corrugated sheet metal. Every time he had a hit record, he told you it was perfectly normal to wake up with a pack of cigarettes on the kitchen table instead of any food and stare out at a highway. He made you think that you, too, could do something besides stand in a field or sit in a truck, but that if you had to, well, that was all right too.

After he died, I thought about the California he knew, and how it left the world long before he did. The clubs he played are all gone. I’ve driven by many of the places where they used to be, and not a trace remains. The Lucky Spot on Edison Highway in Bakersfield is long gone. It’s a parking lot abutting two shuttered antique stores. The ruins aren’t even there anymore. And the place he was from has become almost unlivable. Oildale is so overrun with crime and drugs and destitution that it’s impossible to imagine escaping it. If you walk through it, you feel a bone-deep grinding misery that will physically cause your chest to tighten. And Bakersfield now has the deadliest police force in America. Merle Haggard’s California, the honky-tonks, the Dust Bowl survivors, the labor camps, is fading away.

The physical traces of what molded him have almost been erased, or relegated to museums, which will make him tougher and tougher to understand as he’s slotted into the history books. But I can say this. If you want to get to the soul of the man, you have to look past “Okie From Muskogee,” his sad lapse into jingoism with “The Fightin’ Side of Me,” and his accidental reputation as a conservative, which he spent much of his career undoing. You have to think about the misery he escaped, what it took to survive the Dust Bowl, to survive an oil town or an agricultural town. You have to think about people at the bottom in the towns nobody on TV talks about. You have to think about songs like “They’re Tearing the Labor Camps Down,” which I consider his masterpiece.

It describes the misery working people have to see in America, the despair they have to carry with them. It understands the deep sorrow of feeling left behind and doing everything you can just to hold on. It’s desperately hard to make it in America, and he understood that. His career was a constant reminder of that. He never, ever forgot how tough it is for common people to get by. If you asked the people in my family, most of them one emergency away from going underwater, what they think about Merle Haggard’s passing, they would be very clear with you. The best songwriter ever in country music is now gone.